The Montana Reserved Water Rights Compact Commission (RWRCC) recently released a new report on the Flathead Indian Reserved Water Rights Compact, as directed by Governor Steve Bullock. The report addresses some of the concerns over the compact and lists some of the problems that will likely occur if the compact is not ratified by the 2015 Montana Legislature, when it will go before the legislature for a second time. If passed by the state legislature and thereafter Congress, the compact would quantify the water rights of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT).

The RWRCC, CSKT, and five federal government agencies*, have been negotiating the terms of the Flathead Reservation Federal Reserved Water Compact for over a decade. The compact quantifies the tribal water right for all past, present, and future uses, including non-consumptive uses (in-stream flow), and off-reservation water rights. Five of the seven tribes in the state have already finalized compacts that quantify tribal water rights and the Salish and Kootenai were the remaining two.

The process has been embroiled in controversy since the beginning, and does not seem to be any less controversial now. Water rights and tribal reserved water rights in particular have a contentious history. The Flathead Reservation was established by the Hellgate Treaty in 1855, which reserved 1.3 million acres. Not until Winters v. United States (1908) were the water rights defined as reserved along with land reservations, so several decades passed without any legal legitimacy given to water use by tribes in the reservation. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 and the Allotment Act of 1904 later allowed procurement and settlement by non-Indians, leading to the current situation: today non-Native Americans outnumber Native Americans within the Flathead Reservation. For a history of the fight for water rights for the CSKT, go here.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in response to many cases of litigation over tribal reserved water rights, directed tribes and states to approve compacts quantifying tribal water rights. In November of 2012, the CSKT and RWRCC reached a settlement, and then re-released a revised settlement after several public meetings in February 2013. The compact was brought to the state Legislature, but the bill failed to make it through committee.

It is likely that the failure of the legislature to pass the compact will lead to a very expensive litigation process over the next several years. The report from the state this week has done very little to appease opponents to the compact.

* Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Department of Interior

Sources:

Tristan Scott, Flathead Beacon (12-31-13) Report Released on SCKT Water Rights Compact

Vince Devlin, Missoulian (12-17-13) Report Released on CSKT Water Compact, Impact if Fails, Off-Reservation Claims

Mike Dennison, Missoulian (1-7-14) Water Users Debate Flathead Compact at Legislative Meeting

Stephen Walker, Lewis, Longman and Walker, P.A. (11-10-13) The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Fight for Quantified Federal Water Rights in Montana: A Contentious History

Tuesday, January 7, 2014

Montana releases a new report on the Flathead Indian Reserved Water Rights Compact

Labels:

agriculture,

reserved rights,

water policy,

water quality

Friday, August 23, 2013

Reduced Colorado River releases from Lake Powell

In Salt Lake City last week, the BLM announced that the amount of water released from Lake Powell in water year 2014 (starting in October) will be reduced by 9%. The volume of water released each year is based on guidelines set in 2007 by the Secretary of Interior, which coordinate the management of large reservoirs along the Colorado River, including Lake Powell and Lake Mead. According to the guidelines, "A Shortage Condition exists when the Secretary determines that insufficient mainstream water is available to satisfy 7.5 maf [million acre feet] of annual consumptive use in the Lower Division states." This certainly applies today, and the release from Lake Powell will be 7.48 maf, the lowest release since Glen Canyon Dam was constructed in the 1960s. The BLM projects that Lake Mead levels will decline an additional

eight feet next year as a result of the reduced release from Lake Powell.

Upper Colorado Regional Director Larry Walkoviak said in a statement, "This is the worst 14-year drought period in the last hundred years."

Although the immediate effect on Colorado River water rights holders is small for now, shortages like this are predicted to become more frequent because of changing climate conditions. As Erik Stokstad reports in Science Insider, more water has been promised to users than can be delivered.

Upper Colorado Regional Director Larry Walkoviak said in a statement, "This is the worst 14-year drought period in the last hundred years."

|

| photo credit: Glen Canyon National Recreation Area |

Labels:

climate change,

Colorado River,

conservation,

drought,

water policy,

water rights

Monday, July 29, 2013

Water Infrastructure getting more attention, discourse, and... funding?

Water infrastructure issues are getting more attention across the country as communities struggle with water availability and aging infrastructure issues during the hottest months of the year. States, communities, and private organizations (both non-profit and for-profit) across the US are calling attention to the problem and pledging to commit finances and legislation to try to address these water-related challenges.

Water availability issues, such as those faced in the U.S. West and in rapidly growing regions across the whole country struggle with not only having to maintain and repair their systems to meet the capacity and level of service for which they were designed, but also having to consider future growth and increased strain on water sources as populations expand, or as drought constricts the amount of water available. Aging infrastructure is an issue facing many communities because infrastructure projects built decades ago with large investments are now facing the end of their useful designed life, and the funding for replacements is harder to come by due to strained economic and political conditions. This is having an effect on water quality in many areas, as well as leading to infrastructure failures and water restrictions.

So what does all this mean? Well, it will likely lead to rate increases, a trend which has already begun and will continue. This has implications for lower income communities who already pay a greater share of their income for water services. Rate increases will likely be more noticeable in smaller communities, where the lack of economies of scale precludes the utility from spreading the costs over more people.

This could lead to increased violations of water quality regulations under the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. Both health-based and non-health based violations could go up as a result of water systems not being able to pay for needed infrastructure upgrades.

It could also lead to consolidation of water utilities, especially by larger and more financially viable water systems or even private companies.

The United Nations recently decided that access to safe drinking water was a human right. Here in the United States, we have been fortunate to have relatively cheap access to very high quality drinking water. However, water infrastructure is a huge challenge that casts a spotlight on several related issues including funding for infrastructure projects, affordability and rate setting, environmental justice, water availability and population growth, and climate change.

Water availability issues, such as those faced in the U.S. West and in rapidly growing regions across the whole country struggle with not only having to maintain and repair their systems to meet the capacity and level of service for which they were designed, but also having to consider future growth and increased strain on water sources as populations expand, or as drought constricts the amount of water available. Aging infrastructure is an issue facing many communities because infrastructure projects built decades ago with large investments are now facing the end of their useful designed life, and the funding for replacements is harder to come by due to strained economic and political conditions. This is having an effect on water quality in many areas, as well as leading to infrastructure failures and water restrictions.

So what does all this mean? Well, it will likely lead to rate increases, a trend which has already begun and will continue. This has implications for lower income communities who already pay a greater share of their income for water services. Rate increases will likely be more noticeable in smaller communities, where the lack of economies of scale precludes the utility from spreading the costs over more people.

This could lead to increased violations of water quality regulations under the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. Both health-based and non-health based violations could go up as a result of water systems not being able to pay for needed infrastructure upgrades.

It could also lead to consolidation of water utilities, especially by larger and more financially viable water systems or even private companies.

The United Nations recently decided that access to safe drinking water was a human right. Here in the United States, we have been fortunate to have relatively cheap access to very high quality drinking water. However, water infrastructure is a huge challenge that casts a spotlight on several related issues including funding for infrastructure projects, affordability and rate setting, environmental justice, water availability and population growth, and climate change.

Labels:

Clean Water Act,

climate change,

drinking water,

drought,

Editorial,

Safe Drinking Water Act,

water rights

Friday, May 10, 2013

Think at the Sink for Drinking Water Week!

Originally posted at It's Our Environment.

This week is national drinking water week, and the theme is “What do you know about H2O?” Have you ever considered how water travels from its source and ends up in your kitchen sink?

In 2006, I worked as a volunteer in South Africa. One day I drove across the province to visit a game preserve, leaving the city where I spent most of my time. The contrast between the city and the country was always jarring, and this day I drove farther into the countryside than I’d ever been. Gradually towns dissipated and were replaced by clusters of domed huts. Off to one side of the road, I spotted a woman and her daughter carrying buckets of water into their village. It is hard to describe the dissonance that I felt during this recreational outing to look at elephants with a liter of bottled water tucked into my seat. I’d never had to haul water into my home; I just turned on the tap and safe, clean water poured out. UNICEF estimates that many people in developing countries, particularly women and girls, walk six kilometers a day for water.

The Safe Drinking Water Act authorizes the EPA to set drinking water standards, protect drinking water sources, and work with states and water systems to deliver safe drinking water some 300 million Americans. In the U.S., the last century has seen amazing improvements to drinking water quality. Mortality rates have plummeted and life expectancy has climbed as a result of better science and engineering, public investment in drinking water infrastructure, and the establishment of landmark environmental laws like the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act. Some historians claim that clean water technologies are likely the most important public health intervention of the 20th century.

Today, we can celebrate the fact that the vast majority of people living in the United States have access to safe drinking water. Ninety-two percent of Americans receive clean, safe drinking water every day, and EPA is working to make that number even higher by partnering with states to reduce pollution and improve our drinking water systems. However, we should be aware of new challenges to our drinking water systems like climate change, aging infrastructure and nutrient pollution.

For drinking water week this year, stop and think about how far we’ve come by paying attention each time you turn on your tap.

In 2006, I worked as a volunteer in South Africa. One day I drove across the province to visit a game preserve, leaving the city where I spent most of my time. The contrast between the city and the country was always jarring, and this day I drove farther into the countryside than I’d ever been. Gradually towns dissipated and were replaced by clusters of domed huts. Off to one side of the road, I spotted a woman and her daughter carrying buckets of water into their village. It is hard to describe the dissonance that I felt during this recreational outing to look at elephants with a liter of bottled water tucked into my seat. I’d never had to haul water into my home; I just turned on the tap and safe, clean water poured out. UNICEF estimates that many people in developing countries, particularly women and girls, walk six kilometers a day for water.

The Safe Drinking Water Act authorizes the EPA to set drinking water standards, protect drinking water sources, and work with states and water systems to deliver safe drinking water some 300 million Americans. In the U.S., the last century has seen amazing improvements to drinking water quality. Mortality rates have plummeted and life expectancy has climbed as a result of better science and engineering, public investment in drinking water infrastructure, and the establishment of landmark environmental laws like the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act. Some historians claim that clean water technologies are likely the most important public health intervention of the 20th century.

Today, we can celebrate the fact that the vast majority of people living in the United States have access to safe drinking water. Ninety-two percent of Americans receive clean, safe drinking water every day, and EPA is working to make that number even higher by partnering with states to reduce pollution and improve our drinking water systems. However, we should be aware of new challenges to our drinking water systems like climate change, aging infrastructure and nutrient pollution.

For drinking water week this year, stop and think about how far we’ve come by paying attention each time you turn on your tap.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Utah Governor stops Nevada water sharing agreement

This month, Utah Governor Gary Herbert said he would not sign an agreement that would divvy water under the shared border between Utah and Nevada. This water had been eyed by the thirsty metropolis of Las Vegas a few hours south. The pact was drawn up four years ago in response to a 2004 Congressional order that required the states to reach an agreement before any transfers of water would be permitted in the Snake Valley. The agreement was controversial because of a proposed pipeline enabled by the pact that would send Snake Valley water to Las Vegas. The pipeline spurred protests from farmers, environmentalists, tribes, and ranchers in Utah and parts of Nevada.

This month, Utah Governor Gary Herbert said he would not sign an agreement that would divvy water under the shared border between Utah and Nevada. This water had been eyed by the thirsty metropolis of Las Vegas a few hours south. The pact was drawn up four years ago in response to a 2004 Congressional order that required the states to reach an agreement before any transfers of water would be permitted in the Snake Valley. The agreement was controversial because of a proposed pipeline enabled by the pact that would send Snake Valley water to Las Vegas. The pipeline spurred protests from farmers, environmentalists, tribes, and ranchers in Utah and parts of Nevada.It was not clear whether Gov. Herbert would support the agreement, and he shocked both supporters and critics of the project when he announced his decision. He told the Deseret News, "At the end of the day, when it comes down to those people who have the most to lose — it's their water, their lifestyle, their livelihood — I can't in good conscience sign the agreement. It's that simple."

In Utah, the reaction has been positive. The majority of local citizens and officials at the county level in Millard and Juab counties did not support the water sharing agreement.

The director of Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources said that they are "evaluating all of [their] options in light of Gov. Herbert's decision." A lawsuit could be forthcoming.

Labels:

conservation,

Las Vegas,

water law,

water rights

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

America gets a report card and it's not good

This month, the American Society of Civil Engineers released a 2013 report card for America's infrastructure. Overall, America's GPA is a D+. Dams, Drinking Water, and wastewater each got a D. Inland waterways and levees got a D- each. It is clear that the infrastructure we rely on to transport, distribute, treat, and store water is in pretty poor condition.

Check out the interactive report card at www.infrastructurereportcard.org.

Labels:

efficiency,

infrastructure,

water quality

Water Restrictions Implemented in Colorado

As spring approaches, many Colorado cities, including Colorado Springs, Fort Collins, and Denver, are gearing up for another dry year by instituting tight water restrictions.

In Colorado Springs, watering lawns will be restricted to twice a week for three hours in an effort to bring water usage down 30% from last year. Addresses with odd numbers are allowed to waer on Tuesday and Saturday, even numbers on Sunday and Wednesday. Fines for non-compliance are up to $500. The restrictions go into effect this week, and are typical to the type of restrictions being implemted across the state.

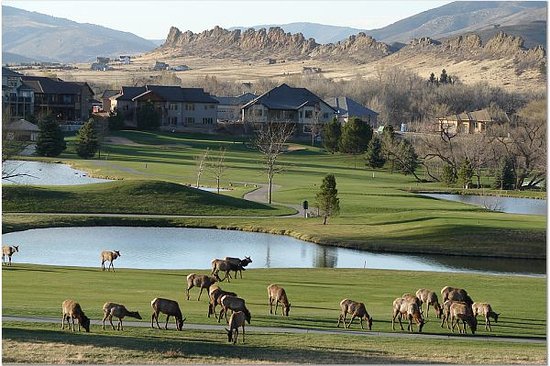

|

| From tripadvisor |

As drought conditions persist (long past the point of "severe" drought classifications), many other municipalities throughout Colorado are having to consider implementing restrictions. Cities that have traditionally kept water use unrestricted, like Loveland, will likely have to follow suit.

The Reporter Herald notes that some coservationists see a silver lining in the drought, which is that perhaps people will begin to understand the real consequences to living in an arid envionment. (However, this blogger is skeptical.)

Labels:

Colorado River,

conservation,

drought,

water policy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)